Early-life nutrition

Research in Context November 25, 2025

Early-life nutrition

Exposures in the womb can affect lifelong health

Nutrition matters, and what young, developing children eat—or are exposed to before birth—can have lasting impacts. This Research in Context feature looks at how scientists have used natural experiments to better understand how early-life nutrition affects lifelong health.

Your family may have pictures of you blowing out a candle on a cake at your first birthday party. Or sitting in a highchair at your first Thanksgiving. Maybe even a shot of you still in the womb, hidden under a maternity shirt, while your mom has an afternoon snack.

These meals happened long before you could remember them. But new research suggests that the nutrition you received from conception through early childhood likely helped lay the foundation for some aspects of health for the rest of your life.

How do we know this? It’s hard to do long-term nutritional experiments using people. And it wouldn’t be ethical to split young kids into two groups and feed one junk food for years. Or, even worse, purposefully expose them to hunger.

But disruptive events in recent history have driven sudden, sharp changes in some people’s diets. These events created conditions that scientists call natural experiments—that is, random events that impact one group of people but not another. By comparing people who lived through such events with similar people who were spared, researchers can gain insights into how such changes affect lifelong health.

Too much too young

Sugar is delicious. Our brains seem hard-wired to crave it. But while it may not do much harm as an occasional treat, excess consumption has been linked with health conditions ranging from obesity to type 2 diabetes.

Current U.S. dietary guidelines recommend that children under the age of 2 consume no added sugar at all. They also encourage people who are pregnant or breastfeeding to eat or drink as little added sugar as possible. Are these recommendations just a buzzkill?

A recent NIH-funded study led by Dr. Tadeja Gracner from the University of Southern California supports the idea that it’s wise advice, not an overreaction. Gracner’s team tapped into a huge natural experiment created by food rationing in the United Kingdom during and immediately after World War II.

During rationing, people’s allotted amount of sugar was similar to that recommended by current U.S. dietary guidelines. However, sugar consumption nearly doubled immediately after rationing ended in September 1953. A similar immediate jump in intake wasn’t seen with other rationed foods.

The researchers examined data from the UK Biobank, which has been tracking about half a million people who were between 40 and 69 years of age when they joined the study between 2006 to 2010.

Gracner and her team compared the risk of developing certain health problems later in life between people who were exposed to sugar rationing at different stages of development and those conceived shortly after rationing ended.

Differences between the two groups started to appear when people were in their mid 50s and increased after age 60. Decades after the end of WWII, people with the longest exposure to rationing during early development had about 35% lower diabetes risk and 20% lower hypertension risk than people who were never exposed to rationing.

People exposed to rationing were also diagnosed with diabetes an average of four years later and hypertension two years later.

The study couldn’t tie any individual’s health problems directly to sugar consumption, but these numbers compare favorably to those seen from the best prevention programs and medications tested to date for diabetes, Gracner says. “If you can minimize sweets in the diet early on, it seems like that could put your child onto a better health trajectory,” she says.

Though it’s not about absolutes, she notes. “It’s concerning that, on average, the majority of toddlers eat sugar daily. Sugar is really hard to avoid in the environment we live in. But in this study, sugar wasn’t banned; it was rationed—at about the levels that are recommended today.”

Small changes, big effects

Recent research that has tracked the diets of expectant mothers in real time supports the results of this natural experiment. For example, a study led by Drs. Tonja Nansel and Leah Lipsky, who study nutrition and health at NIH, compared trends in infant weight and size based on the diet quality of more than 300 pregnant people. They also continued to track these trends for a year after birth.

“Some body fat in infants is important for healthy growth and development,” Lipsky explains. But if a baby is very large at birth, or gains weight in proportion to their height too rapidly in the first year, “that can start to set the child up for having weight problems down the road,” she says. Overweight and obesity can, in turn, lead to a host of health problems in adolescence and adulthood.

Their recent study found both bad news and good news about diet during pregnancy. The bad news was that babies born to mothers who consumed more foods during pregnancy with “empty calories”— with little to no nutritional value like sugar, refined grains, and saturated fat—were more likely to be larger than normal at birth and to gain excess weight after birth faster.

The more of these empty calories consumed during pregnancy, the higher likelihood that the infants would trend toward an overly high growth rate.

But the good news was that even small changes made toward eating fewer empty calories provided a large boost in reduced risk.

“There’s a misconception that if you focus on eating more fruits and vegetables during pregnancy, you’re good,” Lipsky says. “But what this study is saying is that it’s more important to reduce the intake of foods high in empty calories. Having just one less soda or one less bag of chips can have great benefits,” she adds.

Eating healthy during pregnancy can be challenging, Lipsky acknowledges.

But more good news from their study was that eating fewer empty calories while breastfeeding was also associated with healthier infant weights. She noted the opportunity to continue giving kids a healthy start by trying to avoid these foods for the first year of life.

Famine and consequences

Much grimmer than having too much of any one type of food is having not enough food overall. Unfortunately, large-scale famines have occurred many times in relatively recent history. Some of the best known—and best studied—include the Holodomor famine in Ukraine from 1932 to 1933, the Dutch Hunger Winter from 1944 to 1945, and the Great Chinese Famine from 1959 to 1961.

Hunger can kill outright. But how does extreme caloric restriction affect survivors later on? And how does this deprivation affect the course of their health for the rest of their lives?

“These are important questions, about whether the environment of the mother, the nutrition of the mother, could have a long-term impact on their children,” explains Dr. L.H. Lumey, who studies disease trends in populations at Columbia University.

Lumey and his colleagues have been following survivors of the Dutch Hunger Winter since the 1980s. They’ve been comparing long-term health outcomes in people exposed to famine while still in the womb with later-born siblings and members of nearby communities not exposed to famine. This type of natural experiment provides the best, and most ethical way to answer such questions about nutritional deprivation in early life, he explains.

In a recent study, the team looked at how exposure to famine in utero affected biological aging in about 950 people from their database, all of whom had blood samples taken when they were in their late 50s.

The researchers used aging measurements called epigenetic clocks. These measure chemical modifications to DNA collectively called the epigenome. Certain types of epigenetic changes naturally accumulate over time. People who are younger and have lots of these changes are considered to be biologically aging faster than they should be.

Compared with people not exposed to famine in utero, people who were in the womb during the Dutch Hunger Winter were aging faster biologically. And the more weeks of exposure to the famine, the faster their pace of biological aging.

Lumey’s team and others have also found that people exposed to famine have a higher risk of obesity as adults.

Shocks to the system

Other NIH-funded research using natural experiments has shown the lingering effects of hunger on other long-term health outcomes. For example, researchers studying the Holodomor famine found that people exposed to severe malnutrition in the womb had a more than twofold higher likelihood of developing type 2 diabetes later in life than unexposed people of the same age in nearby areas.

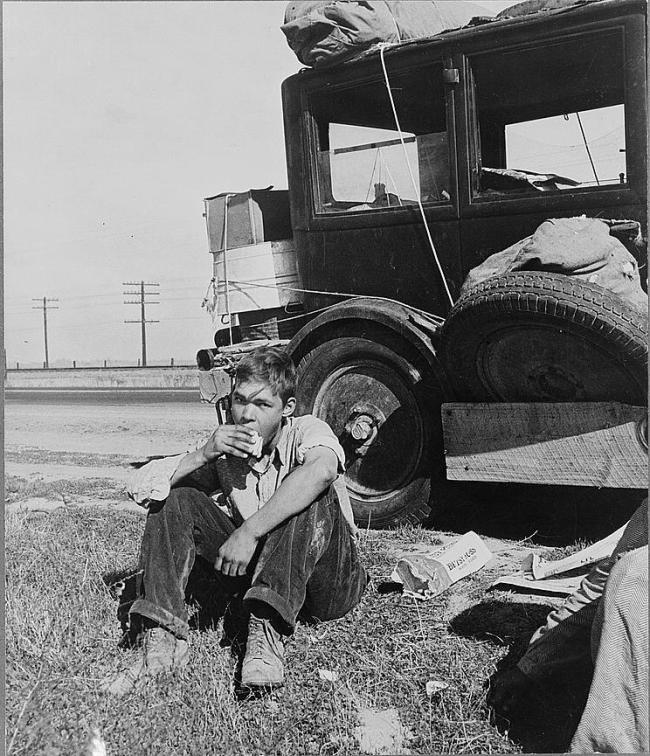

And large-scale societal shocks can cause more than just hunger, explains Dr. Lauren Schmitz, a health economist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. She’s been studying the effects of the Great Depression in the U.S., which began in 1929 and peaked in 1933, on later life health.

“A lot of families were struggling to make ends meet during the Depression,” Schmitz says. This led to undernutrition for many, but also things like eviction, stress and, relatedly, chronic inflammation, which can cause long-term wear and tear on the body, she adds.

Did this challenging environment affect people during early development? To help answer this question, Schmitz and a colleague, Dr. Valentina Duque, linked economic information from the Great Depression to biological data from more than 800 people collected by a large national study called the U.S. Health and Retirement Study (HRS). The HRS, begun in 1992, enrolled people born as long ago as 1931.

Although unemployment rates averaged around 25% at the height of the Depression, the economic pain wasn’t distributed evenly across the country. This created a natural experiment that let the researchers examine whether people exposed to more economic hardship while in the womb had faster rates of epigenetic aging.

Schmitz and Duque found that, compared to people who lived in areas with less economic hardship, those exposed in the womb to the worst economic conditions during the Great Depression showed faster epigenetic aging later in life. They also had epigenetic changes that suggested a higher risk of dying earlier.

These negative effects were only linked to exposure in the womb, not in early childhood. “We know that the epigenome plays a critical role when we’re developing in the womb,” Schmitz explains. “And these epigenetic modifications are sticky.”

Act anytime

None of this is to say that your health is set in stone by your early-life experiences. “We have lots of evidence that changing one’s diet at any stage of life has an effect on health,” Lipsky says.

Large NIH-funded projects like the National Diabetes Prevention Program have found that making healthy dietary changes can lead to substantial improvements in health in just a few months, she explains.

“There are lots and lots of examples like that, where changes in adulthood have real and very rapid improvements in a lot of health risks,” Lipsky says. “It’s not all over by the time you’re born.”

“These early life exposures could influence health trajectories, but they in no way fix destines,” Gracner agrees. “We can modify things with diet, exercise, medications—we can meaningfully change our health for the better at any point in our lives.”

These studies also highlight the importance of helping pregnant people and young children access the most nutritious food possible, Schmitz adds.

“Particularly during tough economic times, social programs that support pregnant women and families may improve the health of children not just in the short run, but throughout their lives,” she says.

“Anything we can do to make it easier to eat healthy during pregnancy and early life is going to have a huge effect on health, because it’s going to impact people during this developmentally sensitive period, and also across their lifespan,” Nansel agrees.

—by Sharon Reynolds

Related Links

- Early-Life Sugar Intake Affects Chronic Disease Risk

- Can We Slow Aging?

- Highly Processed Foods Form Bulk of U.S. Youths' Diets

- Supplement Targets Gut Microbes to Boost Growth in Malnourished Children

- Lower Wealth Linked with Faster Physical and Mental Aging

- Diets Improve but Remain Poor for Most U.S. Children

- Eating Highly Processed Foods Linked to Weight Gain

- School Nutrition Policies Reduce Weight Gain

- Dejunking Your Diet: The Drawbacks of Ultra-Processed Foods

- Dietary Guidelines for Americans

- National Diabetes Prevention Program (CDC)

References

Exposure to sugar rationing in the first 1000 days of life protected against chronic disease. Gracner T, Boone C, Gertler PJ. Science. 2024 Nov 29;386(6725):1043-1048. doi: 10.1126/science.adn5421. Epub 2024 Oct 31. PMID: 39480913.

Genetic analysis of selection bias in a natural experiment: Investigating in-utero famine effects on elevated body mass index in the Dutch Hunger Winter Families Study. Zhou J, Indik CE, Kuipers TB, Li C, Nivard MG, Ryan CP, Tucker-Drob EM, Taeubert MJ, Wang S, Wang T, Conley D, Heijmans BT, Lumey LH, Belsky DW. Am J Epidemiol. 2024 Oct 2;194(7):1959-66. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwae376. Online ahead of print. PMID: 39358993.

Fetal exposure to the Ukraine famine of 1932-1933 and adult type 2 diabetes mellitus. Lumey LH, Li C, Khalangot M, Levchuk N, Wolowyna O. Science. 2024 Aug 9;385(6709):667-671. doi: 10.1126/science.adn4614. Epub 2024 Aug 8. PMID: 39116227.

Famine mortality and contributions to later-life type 2 diabetes at the population level: a synthesis of findings from Ukrainian, Dutch and Chinese famines. Li C, Ó Gráda C, Lumey LH. BMJ Glob Health. 2024 Aug 29;9(8):e015355. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2024-015355. PMID: 39209764.

Accelerated biological aging six decades after prenatal famine exposure. Cheng M, Conley D, Kuipers T, Li C, Ryan CP, Taeubert MJ, Wang S, Wang T, Zhou J, Schmitz LL, Tobi EW, Heijmans B, Lumey LH, Belsky DW. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2024 Jun 11;121(24):e2319179121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2319179121. Epub 2024 Jun 4. PMID: 38833467.

Relationships of pregnancy and postpartum diet quality with offspring birth weight and weight status through 12 months. Lipsky L, Cummings J, Siega-Riz AM, Nansel T. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2023 Dec;31(12):3008-3015. doi: 10.1002/oby.23891. Epub 2023 Sep 20. PMID: 37731285.

In utero exposure to the Great Depression is reflected in late-life epigenetic aging signatures. Schmitz LL, Duque V. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022 Nov 15;119(46):e2208530119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2208530119. Epub 2022 Nov 8. PMID: 36346848.