An LSD analogue for treating psychiatric diseases

May 6, 2025

An LSD analogue for treating psychiatric diseases

At a Glance

- Researchers designed a non-hallucinogenic analogue of LSD that had antidepressant and numerous cognitive benefits in mice.

- The resulting drug could be a safer alternative to psychedelics for treating neuropsychiatric diseases like schizophrenia.

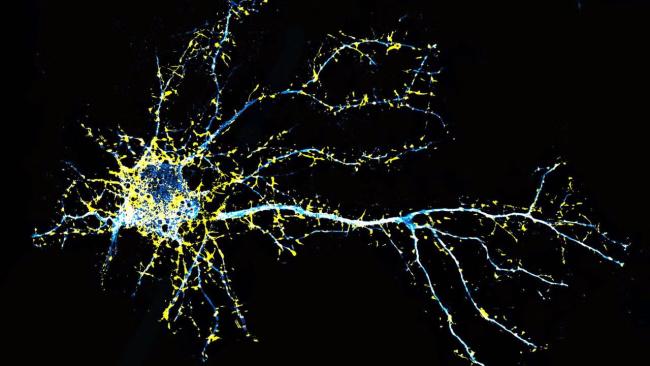

Certain psychiatric diseases, such as depression and schizophrenia, feature a loss of structures called dendritic spines from neurons. Dendritic spines form the receiving end of synapses, or connections between neurons. Psychedelic drugs, such as lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), have shown promise relieving some symptoms of these psychiatric diseases. The drugs act by binding certain serotonin receptors in the brain to promote the growth of new spines and formation of new synapses. This process is known as neuroplasticity.

But psychedelic drugs can also cause other effects. Their hallucinogenic side effects make them unsafe for many people. This is particularly true for people with schizophrenia or a family history of psychosis. Hallucinations and delusions are a symptom of schizophrenia that hallucinogenic drugs can make worse.

Previous research showed that modification of a psychedelic drug called N,N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT) could reduce its hallucinogenic potential while retaining its ability to promote plasticity. The modified compound bound to the same serotonin receptors as DMT, but in a slightly different manner. LSD is even more effective at promoting plasticity than DMT. Thus, a research team led by Dr. David Olson at the University of California, Davis set out to design a drug that retained LSD’s ability to promote neuron growth without the hallucinogenic potential. Results of their effort, which was funded in part by NIH, appeared in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on April 14, 2025.

Guided by the DMT results, the team tried switching the places of two atoms in LSD. This resulted in a compound that had the same 3D structure as LSD but altered the way it bound to its target receptor, similar to the modified DMT. The researchers developed a procedure for synthesizing the compound, which they named JRT, from commercially available starting materials.

The team tested JRT’s ability to bind different receptors found in the central nervous system. While LSD can bind to many receptor types, JRT bound only to serotonin receptors. Interactions with a specific serotonin receptor, the 5-HT2A receptor, are responsible for both the plasticity-promoting and hallucinogenic effects of psychedelics. JRT was potent at activating this receptor, although to a lesser extent than LSD.

JRT promoted the growth of dendritic spines in cultured rat neurons. It did so as well or better than LSD and the antipsychotic drug clozapine. When the team administered JRT to mice, it increased the density of dendritic spines and synapses. A single dose of JRT in mice could restore the loss of dendritic spine density caused by chronic exposure to stress hormones.

Further mouse testing suggested that JRT had much lower hallucinogenic potential than LSD. JRT did not produce responses in mice that are believed to correlate with the hallucinogenic action of LSD. Pretreating mice with JRT also blocked LSD from producing these responses. This suggests that they bind to the same receptor. Unlike LSD, JRT did not cause sensory alterations in a mouse model. Nor did it activate genes in the brain associated with schizophrenia.

JRT also produced improvements in mice in tests designed to detect potential antidepressant effects. Moreover, it did so at doses 100-fold lower than ketamine, a drug used for treatment-resistant depression. JRT promoted cognitive flexibility as well, which is often impaired in schizophrenia.

Current medications for schizophrenia are effective at treating hallucinations and delusions. But they are less effective at treating other symptoms, like the inability to feel pleasure and impaired cognitive function. These results suggest that JRT might be able to safely treat these symptoms as well. More broadly, they show continued progress in designing non-hallucinogenic psychedelic analogues.

“The development of JRT emphasizes that we can use psychedelics like LSD as starting points to make better medicines,” Olson says. “JRT has extremely high therapeutic potential. Right now, we are testing it in other disease models, improving its synthesis, and creating new analogues of JRT that might be even better.”

—by Brian Doctrow, Ph.D.

Related Links

- How Psychedelic Drugs Alter the Brain

- Research in Context: Treating depression

- How Psychedelic Drugs May Help with Depression

- Biosensor Advances Drug Discovery

- Revealing Gene Regulation in The Brain

- Protein Structure Reveals How LSD Affects the Brain

- Psychedelic and Dissociative Drugs

- Psilocybin for Mental Health and Addiction: What You Need to Know

- Mental Health Medications

- Schizophrenia

References

Molecular design of a therapeutic LSD analogue with reduced hallucinogenic potential. Tuck JR, Dunlap LE, Khatib YA, Hatzipantelis CJ, Weiser Novak S, Rahn RM, Davis AR, Mosswood A, Vernier AMM, Fenton EM, Aarrestad IK, Tombari RJ, Carter SJ, Deane Z, Wang Y, Sheridan A, Gonzalez MA, Avanes AA, Powell NA, Chytil M, Engel S, Fettinger JC, Jenkins AR, Carlezon WA Jr, Nord AS, Kangas BD, Rasmussen K, Liston C, Manor U, Olson DE. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2025 Apr 22;122(16):e2416106122. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2416106122. Epub 2025 Apr 14. PMID: 40228113.

Funding

NIH’s National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS), National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), and National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA); University of California, Davis; Camille and Henry Dreyfus Foundation; The Boone Family Foundation; Hope for Depression Research Foundation; Pritzker Neuropsychiatric Disorders Research Consortium; David F. And Margaret T. Grohne Family Foundation; L.I.F.E. Foundation; Chan Zuckerberg Initiative; National Science Foundation; G. Harold & Leila Y. Mathers Foundation; Delix Therapeutics.