Source of gastrointestinal problems in myotonic dystrophy

January 13, 2026

Source of gastrointestinal problems in myotonic dystrophy

At a Glance

- Research in mice identified why people with the most common form of adult-onset muscular dystrophy often have gastrointestinal problems.

- The findings could lead to treatments that relieve gastrointestinal symptoms in people with this condition.

Roughly one in 8,000 people lives with the most common form of adult-onset muscular dystrophy, called myotonic dystrophy type 1 (DM1). It’s caused by a mutation in the DMPK gene. The mutation interferes with muscleblind-like (MBNL) proteins. These proteins help process RNAs into the mature forms that cells need for their normal function.

DM1’s main symptoms include muscle weakness and difficulty relaxing muscles after they contract. But people with DM1 also commonly report distressing gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms. These GI symptoms are not as well understood as the condition’s effects on the skeletal muscles that move our bodies.

An NIH-funded research team led by Dr. Thomas Cooper at Baylor College of Medicine investigated the cause of GI symptoms in people with DM1. The scientists generated a mouse model in which two genes that code for MBNL proteins could be disabled within smooth muscle cells. Smooth muscle controls involuntary movements in the intestines and many other organs. The results were published on December 11, 2025, in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

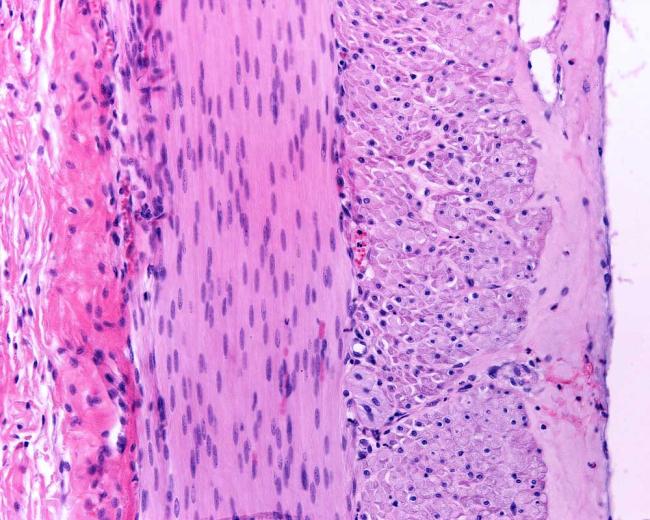

Compared to control mice, substances in the mouse model moved much more slowly through the small and large intestines. This occurred despite no clear defects in the structure of their intestinal tissues.

The team noted that in the small and large intestines of the mouse model, the smooth muscle was thicker than normal. This was not clearly due to differences in muscle cell size or number. It might instead be a result of dysfunctional cell growth and division. The small intestine was also shorter in the mouse model despite there being no differences in body size between the mouse model and control mice.

The researchers isolated intestinal segments from the mice and measured their ability to contract. The small intestine from the mouse model contracted much more than normal and relaxed more slowly. The large intestine from the mouse model was more contracted before being induced to contract. It also exhibited less forceful contractions when induced to contract, which may be due to muscle fatigue.

Muscle contraction is triggered when a protein called Mlc20, part of the molecular motor that drives muscle contraction, undergoes a process called phosphorylation. The researchers found that Mlc20 in the small and large intestines of the DM1 mouse model was much more phosphorylated than in genetically normal mice. This is consistent with the muscle being in a state of constant contraction.

To understand how defective MBNL could lead to excess muscle contraction, the team sequenced RNAs from small and large intestine cells from people with DM1. They found that hundreds of RNA molecules had abnormal sequences. Many of the abnormal RNAs found in human tissues were also seen in the mouse model. RNAs important for muscle contraction and Mcl20 phosphorylation were notable among the abnormal RNAs in both the human DM1 samples and the DM1 mouse model.

The results suggest that the dysfunctional MBNL proteins of people with DM1 may cause their intestinal muscles to have difficulty relaxing after contraction. This effect is similar to that observed in skeletal muscle in DM1. This knowledge could lead to treatments that lessen DM1 GI symptoms by reducing intestinal muscle contraction.

“By creating a GI-specific mouse model and comparing it to human tissue, this study not only uncovered a key mechanism but points at new ways to develop treatments that could make a difference in people living with DM1,” Cooper says.

—by Brandon Levy

Related Links

- Small molecule targets cause of adult onset muscular dystrophy

- Getting a grip on gastroparesis

- Keeping your gut in check

- Myotonic dystrophy

- Muscular dystrophy

- Muscular dystrophy (CDC)

References

MBNL loss of function in smooth muscle as a model for myotonic dystrophy associated gastrointestinal dysmotility. Peterson JAM, Frias JA, Miller AN, Soni KG, Zhang Y, Xia Z, Day JW, Preidis GA, Cooper TA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.. 2025 Dec 16;122(50):e2522788122. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2522788122. Epub 2025 Dec 11. PMID: 41379996.

Funding

NIH’s National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS), National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS), National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), National Cancer Institute (NCI), and Office of the Director (OD); Texas Children’s Hospital; Myotonic Dystrophy Foundation; Marigold Foundation; Jack and Ben Kelly Fund.