You are here

May 11, 2016

Zika and Beyond: Communicating about Crises

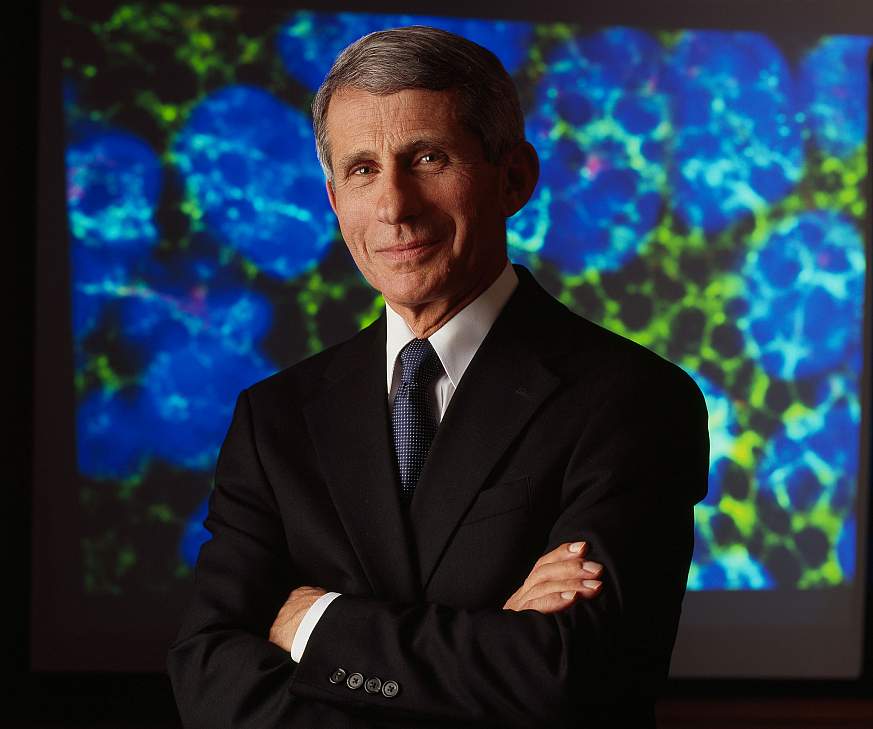

By Anthony S. Fauci, M.D.

Director, NIH's National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID)

During the Ebola outbreak, we admitted two patients infected with the virus to the NIH Clinical Center. People would ask me, “My goodness, are you putting us at great risk?” So I would ask them, “How did you get to work this morning?” They would answer by saying something to the effect of, “Well, I got on the Beltway and drove to the NIH.” This is a high-speed road that encircles Washington, DC, and carries more than 200,000 vehicles per day. I would point out, “Well, your commute posed a greater risk to you than an Ebola patient at the Clinical Center.”

We live in a world where we take risks every day. When you have been taking a risk every day, for the last 20 or 30 years, you may be fully aware of the risk, but you have learned to live with it and it does not bother you.

However, it is very interesting to me how people react when they are confronted with a new risk. When a new risk emerges, especially if it is highly publicized, people often start to consider the new risk to be more significant than others that, in reality, pose a greater threat. This is human nature. We saw it with Ebola, we saw it here in Washington, D.C., with the anthrax attacks, and we are starting to see it now with Zika.

Zika virus is not actually new. It was first recognized in 1947 in a monkey in the Zika forest of Uganda. It was not known to infect humans until 1952, and it stayed under the radar screen for a long time. That was understandable. The virus circulated relatively unnoticed in areas of Africa and Southeast Asia until 2007, when it caused an outbreak on the Yap Islands in Micronesia. In 2013, the virus caused a much larger outbreak in French Polynesia. Despite this spread, few people paid much attention to the virus because the disease it caused was thought to be mild.

Now, of course, the situation has changed. The current outbreak that started in Brazil last year has provided new evidence that Zika virus can also cause a serious birth defect called microcephaly in babies born to infected mothers. Zika virus also has now been associated with Guillain-Barré syndrome. Now, Zika has our attention.

Many people are now hearing or reading that Zika is in their state. By the end of April, the CDC had identified Zika cases in 43 states. Some people are starting to ask whether they should travel to certain states that have reported cases of Zika. In that regard, it is important to note that none of these infections was acquired locally through infected mosquitoes.* So far, all of these cases have been acquired through travel (or sexual contact with someone who has traveled) to countries or territories where Zika is circulating locally.

While we have not yet seen locally acquired cases of Zika in the continental United States, this almost certainly will occur. It is unlikely that these locally acquired cases will become sustained and widespread. However, we must be prepared to deal with them. Certainly, there is no reason to panic. We are going to have to do a lot to educate the public about what the risk is and what the risk is not, and to help people keep the risk in perspective. We should all recall what happened in the United States not so long ago, when an individual came from Liberia and was hospitalized with Ebola in Texas, and then two nurses became infected when caring for him. This sad situation sparked a panic that there was going to be a major outbreak of Ebola in the United States. In reality, there was virtually no chance that would happen.

As concerning as the Zika virus is, we must remember and remind people that it is just the latest disease in a perpetual series of emerging and reemerging infectious disease threats. The timeless threat of new diseases—or old diseases that start to appear in new places or new ways—is now amplified by factors such as urban crowding, international travel, and other human behaviors.

An evolving situation such as the current Zika outbreak, in which there are still unknowns, will create a lot of concern and even panic on the part of some people. We in the public health sector must be crystal clear in articulating exactly what we know and what we still need to know about the threat, and in helping people understand how this new risk compares to risks they willingly assume every day. With that perspective, people will be better able to understand what rational steps they can take to protect themselves.

*This was originally posted on May 12, and information continues to evolve on Zika. Please see http://syndication.nih.gov/zika.htm for the most recent information about the virus. The communication principles discussed here are still relevant.

Have you had situations where you delivered health information that was difficult to keep in perspective? Send us some examples of how you handled these situations. E-mail us at sciencehealthandpublictrust@mail.nih.gov.