How excess niacin may promote cardiovascular disease

March 12, 2024

How excess niacin may promote cardiovascular disease

At a Glance

- A metabolite of niacin (vitamin B3) was associated with elevated risk of heart attack and stroke, likely due to inflammation in arteries.

- The findings suggest new measures that may prevent or treat cardiovascular disease and raise concerns about the health effects of too much niacin.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is disease of the heart and blood vessels. CVD is a leading cause of death in the United States for both men and women. Despite advances in prevention and treatment, it remains widespread. This suggests that there may be risk factors that are not yet recognized.

To investigate, an NIH-funded research team, led by Dr. Stanley Hazen at the Cleveland Clinic, searched for products of metabolism that might contribute to CVD risk. The results appeared in Nature Medicine on February 19, 2024.

The team analyzed blood plasma from more than 1,100 people for molecules associated with major adverse cardiac events, such as heart attacks and strokes. They identified two such molecules, 2PY and 4PY. Both of these are produced when the body breaks down excess niacin.

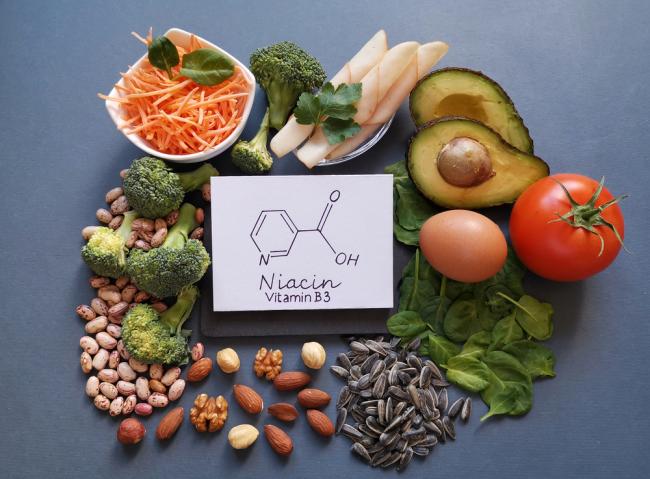

Niacin, also known as nicotinic acid or vitamin B3, is an essential part of the diet. Many countries require that staple foods like cereals, flour, oats, and grains be fortified with niacin to prevent deficiency. In the United States, niacin must be added to “enriched” foods. The recommended amount of niacin is 14–18 mg/day for adults.

High–dose niacin (1,500–2,000 mg/day) was also one of the first cholesterol-lowering drugs. But studies into the effects of niacin on heart attack or stroke, unlike newer cholesterol-lowering drugs, have had mixed results. Researchers hadn’t understood why.

The researchers examined 2PY and 4PY levels in two other groups, one American and one European, totaling more than 3,000 people. They confirmed that elevated levels of either molecule were associated with increased risk of major cardiac events. People with 2PY or 4PY levels in the top 25% had 1.6-2 times the risk of major cardiac events over the next three years as those with levels in the bottom 25%, even after controlling for other CVD risk factors.

Levels of both 2PY and 4PY were associated with variants in a gene called ACMSD. The team found that levels of another protein, called VCAM-1, were also associated with ACMSD variants. Furthermore, VCAM-1 levels correlated with 2PY and 4PY levels.

VCAM-1 is known to help white blood cells stick to the walls of blood vessels as part of the inflammatory response. This contributes to the formation of plaque in arteries. Injecting mice with 4PY, but not 2PY, increased the amount of VCAM-1 on the walls of blood vessels and the number of stuck white blood cells.

These findings suggest that excess niacin may be a risk factor for CVD. When excess niacin is broken down into 4PY, this breakdown product activates inflammatory pathways that are known to promote plaque formation in arteries. This may increase the risk of major cardiac events.

“Niacin’s effects have always been somewhat of a paradox,” Hazen says. “Despite niacin lowering cholesterol, the clinical benefits have always been less than anticipated based on the degree of LDL [cholesterol] reduction. This led to the idea that excess niacin caused unclear adverse effects that partially counteracted the benefits of LDL lowering. We believe our findings help explain this paradox.”

The study results could lead to better assessment of CVD risk. They also highlight the importance of further research on the health effects of supplemental niacin.

—by Brian Doctrow, Ph.D.

*Editor's note: The fifth paragraph was reworded because it originally stated that previous studies found high-dose niacin did not lower the risk of heart attack or stroke. Previous studies, however, had complicating factors and yielded conflicting results. On September 5, 2024, the journal published two commentaries as well as an author response discussing these issues. These have been added to the Reference section below.

Related Links

- Erythritol and Cardiovascular Events

- Irregular Sleep Patterns May Raise Risk of Heart Disease

- Stress Links Poverty to Inflammation and Heart Disease

- Eating Red Meat Daily Triples Heart Disease-Related Chemical

- How Dietary Factors Influence Disease Risk

- Healthy Body, Happy Heart: Improve Your Heart Health

- Niacin: Fact Sheet for Consumers

- Coronary Heart Disease

- Heart-Healthy Living

- Heart Health and Aging

References

A terminal metabolite of niacin promotes vascular inflammation and contributes to cardiovascular disease risk. Ferrell M, Wang Z, Anderson JT, Li XS, Witkowski M, DiDonato JA, Hilser JR, Hartiala JA, Haghikia A, Cajka T, Fiehn O, Sangwan N, Demuth I, König M, Steinhagen-Thiessen E, Landmesser U, Tang WHW, Allayee H, Hazen SL. Nat Med. 2024 Feb;30(2):424-434. doi: 10.1038/s41591-023-02793-8. Epub 2024 Feb 19. PMID: 38374343.

Niacin, food intake and cardiovascular effects. Guyton JR, Boden WE. Nat Med. 2024 Sep;30(9):2444-2445. doi: 10.1038/s41591-024-03220-2. Epub 2024 Sep 5. PMID: 39237629.

Cardiovascular safety of vitamin B(3) administration. Schreiber S, Waetzig GH, Laudes M, Rosenstiel P. Nat Med. 2024 Sep;30(9):2446-2447. doi: 10.1038/s41591-024-03219-9. Epub 2024 Sep 5. PMID: 39237628.

Reply to Guyton, J. R. & Boden, W. E.; Schreiber, S. et al. Tang WHW, DiDonato JA, Allayee H, Hazen SL. Nat Med. 2024 Sep;30(9):2448-2449. doi: 10.1038/s41591-024-03222-0. Epub 2024 Sep 5. PMID: 39237627.

Funding

NIH’s National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), Office of Dietary Supplements (ODS), National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), and National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS); Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft; Charité–Universitätsmedizin Berlin; Berlin Institute of Health; Sanofi-Aventis Deutschland GmbH.