Social acceptance helps mental health after war trauma

June 25, 2019

Social acceptance helps mental health after war trauma

At a Glance

- Researchers found that acceptance and support from community and family may lessen the toll of mental health conditions experienced by former child soldiers.

- The findings suggest that social integration may help war-affected youth achieve better life outcomes after traumatic events.

A traumatic event is a shocking, scary, or dangerous experience that affects you emotionally. During war, people can be exposed to many different traumatic events. That raises the chances of developing mental health problems—like post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, and depression—and poorer life outcomes as adults.

In some violent armed conflicts, children may be separated from their families and communities by armed groups. These “child soldiers” can witness or participate in killings and experience other traumatic events. In addition to the psychological trauma and physical injuries, many former child soldiers face rejection from family and community after the war.

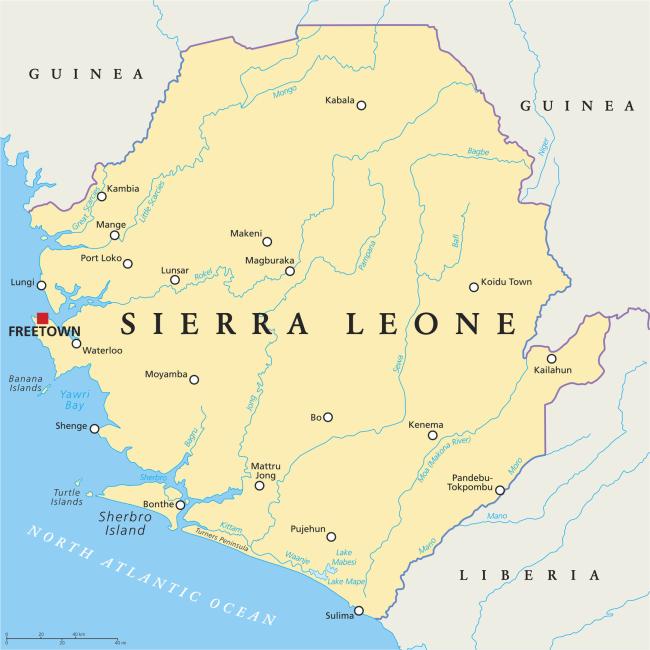

To investigate the role of community and family support in these former soldiers, a team led by Dr. Theresa S. Betancourt at Boston College analyzed data from a 15-year study of more than 500 former male and female child soldiers who participated in Sierra Leone’s Civil War from 1991 to 2002. Several warring factions abducted children and forced them into armed groups. An estimated 15,000 to 22,000 boys and girls of all ages were subject to sexual violence, forced use of alcohol and drugs, hard physical labor, and acts of violence until the war ended.

The participants were interviewed four times (in 2002, 2004, 2008 and 2016 to 2017) about their involvement with armed groups, exposure to violence in the war, and family and community relationships after the war. Interviewers also asked them questions to gauge their mental health status and psychological adjustment. The research was supported by NIH’s Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). Results were published online on June 6, 2019, in the Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry.

The researchers were able to define three developmental trajectories. Some children were socially protected. Others had improving social integration—they were highly stigmatized and had low community and family acceptance when the study began but had a large decrease in stigma and increase in acceptance after two years. A third, socially vulnerable group was highly stigmatized and had low family and community acceptance and only marginal improvements in stigma and acceptance over time.

Members of the socially vulnerable group were about twice as likely as those in the socially protected group to have high levels of anxiety and depression. They were three times more likely to have attempted suicide and over four times more likely to have been in trouble with the police. Those in the improving social integration group weren’t significantly more likely than the socially protected group to experience any negative outcomes, apart from a slightly higher level of trouble with police.

“Sierra Leone’s child soldiers experienced violence and loss on a scale that’s hard to comprehend,” says study author Dr. Stephen Gilman of NICHD. “Our study provides evidence that there may be steps we can take to modify the post-war environment to alleviate mental health problems arising from these experiences.”

Related Links

- Coping With Traumatic Events

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

- Anxiety Disorders

- Depression

- Understand Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (VA)

- Dealing With Trauma: Recovering From Frightening Events

References

Stigma and Acceptance of Sierra Leone's Child Soldiers: A Prospective Longitudinal Study of Adult Mental Health and Social Functioning. Betancourt TS, Thomson DL, Brennan RT, Antonaccio CM, Gilman SE, VanderWeele TJ. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019 Jun 6. pii: S0890-8567(19)30392-2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2019.05.026. [Epub ahead of print] PMID: 31176749.

Funding

NIH’s Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD)