You are here

August 23, 2022

Antibody treatment protects adults against malaria

At a Glance

- A single low dose of an experimental monoclonal antibody safely and effectively prevented malaria infection in a small clinical trial.

- If confirmed in larger studies, this antibody-based approach could help block the spread of this life-threatening illness.

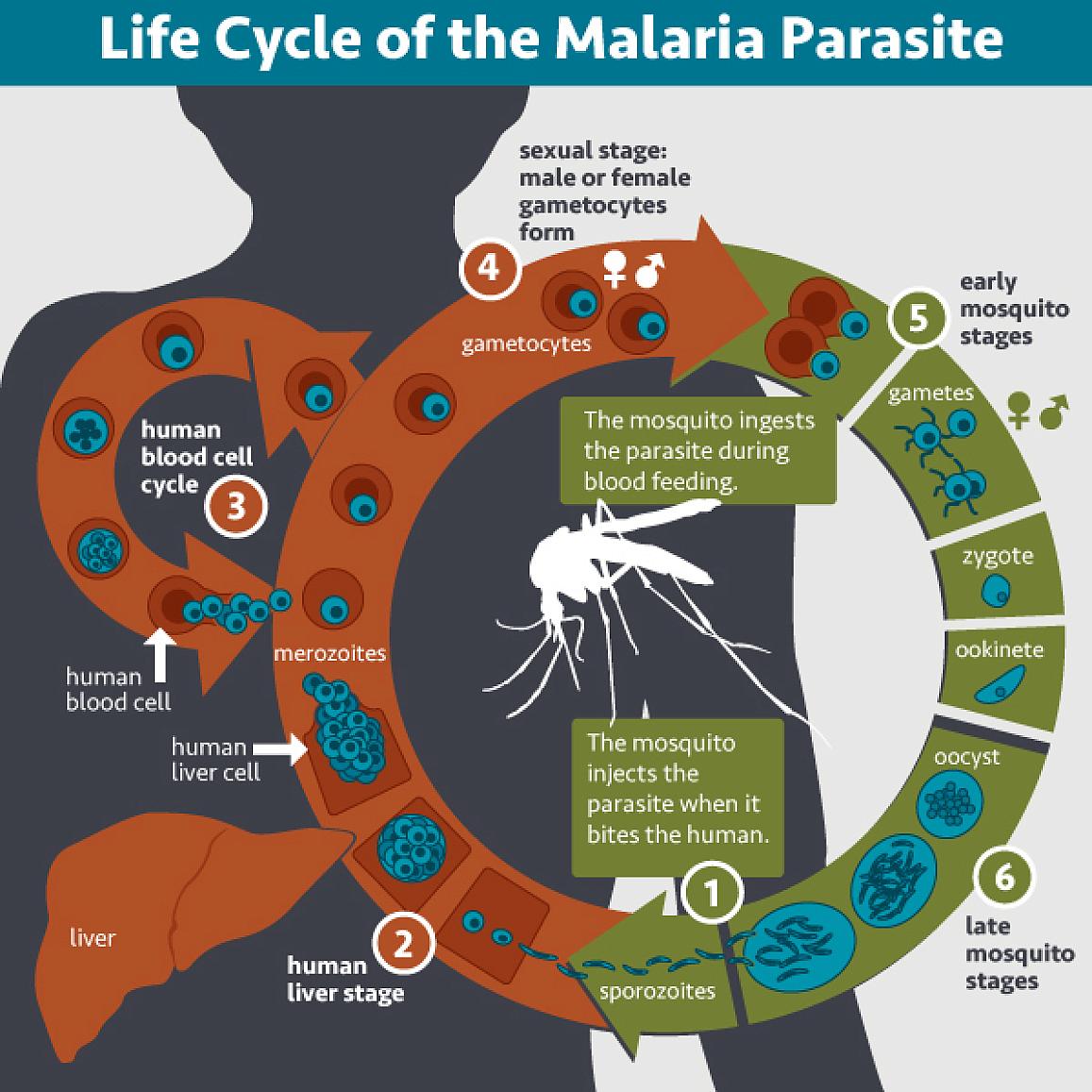

Malaria is a mosquito-borne disease that causes more childhood deaths and illness worldwide than any other single infectious agent. Last year, the World Health Organization endorsed a malaria vaccine for use in at-risk children. But the vaccine is only partially effective in preventing severe malaria. Researchers have been pursuing new approaches for the prevention and elimination of malaria.

Scientists from NIH’s Vaccine Research Center set out to develop a laboratory-made antibody, called a monoclonal antibody, to neutralize the disease-causing parasite before it can infect the liver and take hold in the body. They created a monoclonal antibody from the blood of a volunteer who received an experimental malaria vaccine. It latches onto the same part of the malaria parasite that’s targeted by the vaccine. The researchers then developed a modified antibody, called L9LS, to provide more prolonged protection.

L9LS was given to 17 healthy adults in the U.S. to test its safety and effectiveness. Five participants received subcutaneous (under the skin) injections of the antibody. The rest received intravenous, or IV, infusions at varying doses. Two to six weeks later, in a safely controlled setting, the volunteers allowed malaria-infected mosquitoes to bite their forearms. A control group of six volunteers were likewise exposed to malaria but did not receive L9LS. Medical staff closely monitored and promptly treated any participants who became ill. Findings appeared on August 4, 2022, in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The researchers found that L9LS fully protected 15 of 17 (88%) participants from malaria infection during the 21-day challenge period. In contrast, all six control participants developed malaria.

All seven volunteers who received low- or medium-dose infusions of L9LS were protected from infection. One in five of those receiving a very low-dose infusion became infected. Importantly, only one in five who received low-dose injections of L9LS became infected with malaria. The researchers note that delivering monoclonal antibodies as a single injection is likely more cost-effective and feasible than by IV infusion, especially for treating children.

L9LS was safe and well-tolerated, with no significant adverse events. Clinical trials are now underway in Mali and Kenya, where malaria is widespread. Researchers are testing to see if injections of L9LS can protect infants and young children from malaria for up to 12 months.

“This is the first demonstration that a monoclonal antibody can provide protection with a low dose given by the subcutaneous route. These initial data have potentially important implications for widespread clinical use and ultimately reaching the goal of eliminating malaria,” says VRC’s Dr. Robert Seder, who led the development of L9LS. “We look forward to results in larger field studies that will help establish safety and efficacy and define the lowest effective dose.”

Related Links

- Monoclonal Antibody Prevents Malaria in Early Trial

- Malaria Vaccines Provide Strong and Lasting Immunity

- Universal Mosquito Vaccine Tested

- Engineering Malaria Resistance in Mosquitoes

- Block the Buzzing, Bites, and Bumps

- Malaria

- NIH Vaccine Research Center

References: Low-Dose Subcutaneous or Intravenous Monoclonal Antibody to Prevent Malaria. Wu RL, Idris AH, Berkowitz NM, Happe M, Gaudinski MR, Buettner C, Strom L, Awan SF, Holman LA, Mendoza F, Gordon IJ, Hu Z, Campos Chagas A, Wang LT, Da Silva Pereira L, Francica JR, Kisalu NK, Flynn BJ, Shi W, Kong WP, O'Connell S, Plummer SH, Beck A, McDermott A, Narpala SR, Serebryannyy L, Castro M, Silva R, Imam M, Pittman I, Hickman SP, McDougal AJ, Lukoskie AE, Murphy JR, Gall JG, Carlton K, Morgan P, Seo E, Stein JA, Vazquez S, Telscher S, Capparelli EV, Coates EE, Mascola JR, Ledgerwood JE, Dropulic LK, Seder RA; VRC 614 Study Team. N Engl J Med. 2022 Aug 4;387(5):397-407. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2203067. PMID: 35921449.

Funding: NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID).