You are here

May 13, 2025

Involuntary responses reflect severity of tinnitus symptoms

At a Glance

- By analyzing subtle facial movements, researchers found ways to objectively measure the severity of tinnitus and sound sensitivity disorder symptoms.

- Better measures of symptom severity could aid in evaluating potential treatments.

About 12% of adults experience chronic tinnitus, a persistent ringing, buzzing or clicking sound in the ears. This is often accompanied by heightened sensitivity to sounds, called hyperacusis, in which sounds that don’t bother most people become uncomfortable. There are currently no ways to measure these symptoms objectively. Instead, doctors must rely on subjective questionnaires to gauge disease severity.

A research team led by Dr. Daniel Polley at Massachusetts Eye and Ear examined whether certain sounds could elicit unconscious or involuntary responses. These responses, they reasoned, might predict the severity of tinnitus and hyperacusis. They compared 47 people with chronic tinnitus or sound sensitivity to 50 people without either condition. Results of the study, which was funded in part by NIH, appeared in Science Translational Medicine on April 30, 2025.

The team first recorded electrical activity in the participants’ brains. This allowed them to measure how neural activity increases with sound intensity, which is called central auditory neural gain. Excess central auditory gain has been proposed as a possible cause of tinnitus and hyperacusis. They found that people with disordered hearing had higher central auditory gain on average than people with normal hearing. But central gain didn’t correlate with symptom severity as measured by standard questionnaires.

Emotional stimuli can elicit unconscious physiological responses. For example, pupil dilation can be one sign of increased arousal. The researchers recorded participants’ faces while they listened to various emotionally evocative sounds, such as music or unpleasant animal noises. Pupil diameter increased sharply about a half-second after sound onset. The less pleasant the sound, the greater the dilation. In participants with disordered hearing, pupils dilated more for all sounds than in those with normal hearing. Also, pupil dilation was correlated with how severe people reported their tinnitus and hyperacusis to be.

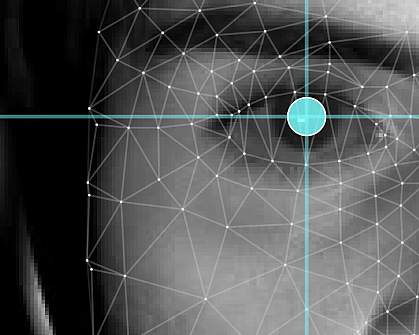

The researchers used recent advances in computer vision to quantify facial movements. A face mesh was fit frame-by-frame, with additional analysis of local image statistics. The system highlights otherwise covert movements in the recording such as a nostril flare (2s), a jaw clench (3s), and an eyebrow twitch (4.5s). Mass Eye and Ear

In addition, the team was able to identify subtle involuntary facial movements that occurred in response to the sounds. Pleasant sounds elicited movements around the corners of the mouth. Unpleasant sounds triggered tightening of the muscles around the eyes and forehead. These facial movements tended to be less pronounced in participants with disordered hearing.

Pupil dilation and facial movements accurately reflected questionnaire scores for tinnitus severity. They also tracked with hyperacusis severity scores, although not as accurately as with tinnitus severity.

The results suggest that disrupted sound processing in people with tinnitus and hyperacusis causes unconscious physiological responses. With further development, this system might be used in health clinics and clinical trials to objectively measure the severity of these conditions. Better measures of symptom severity would improve our ability to assess potential treatments for these conditions.

“What’s really exciting is this vantage point into tinnitus severity didn’t require highly specialized brain scanners; instead, the approach was relatively low-tech,” Polley says.

—by Brian Doctrow, Ph.D.

Related Links

- Cochlear Nerve Damage Associated with Tinnitus

- Hearing Aids Slow Cognitive Decline in People At High Risk

- Diagnosing Hidden Hearing Loss

- SARS-Cov-2 Infection of The Inner Ear

- Ringing in Your Ears? Get the Buzz on Tinnitus

- Tinnitus

References: Objective autonomic signatures of tinnitus and sound sensitivity disorders. Smith SS, Jahn KN, Sugai JA, Hancock KE, Polley DB. Sci Transl Med. 2025 Apr 30;17(796):eadp1934. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.adp1934. Epub 2025 Apr 30. PMID: 40305576.

Funding: NIH’s National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD); American Speech-Language-Hearing Foundation.