Computer-designed proteins may protect against coronavirus

September 29, 2020

Computer-designed proteins may protect against coronavirus

At a Glance

- Researchers designed “miniproteins” that bound tightly to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and prevented the virus from infecting human cells in the lab.

- More research is underway to test the most promising of the antiviral proteins.

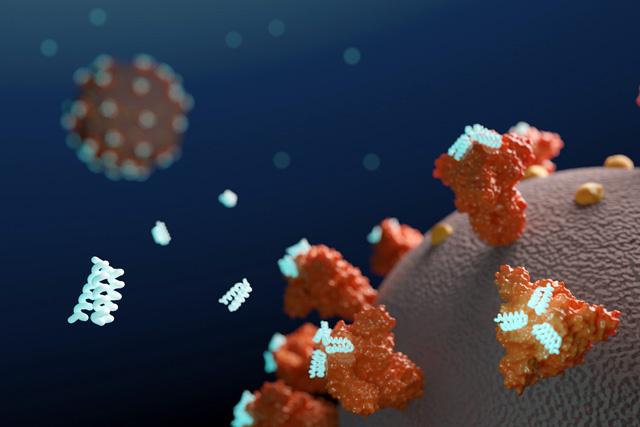

The surface of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, is covered with spike proteins. These proteins latch onto human cells, allowing the virus to enter and infect them. The spike binds to ACE2 receptors on the cell surface. It then undergoes a structural change that allows it to fuse with the cell. Once inside, the virus can copy itself and produce more viruses.

Blocking entry of SARS-CoV-2 into human cells can prevent infection. Researchers are testing monoclonal antibody therapies that bind to the spike protein and neutralize the virus. But these antibodies, which are derived from immune system molecules, are large and not ideal for delivery through the nose. They’re also often not stable for long periods and usually require refrigeration.

Researchers led by Dr. David Baker of the University of Washington set out to design synthetic “miniproteins” that bind tightly to the coronavirus spike protein. Their study was funded in part by NIH’s National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). Findings appeared in Science on September 9, 2020.

The team used two strategies to create the antiviral miniproteins. First, they incorporated a segment of the ACE2 receptor into the small proteins. The researchers used a protein design tool they developed called Rosetta blueprint builder. This technology allowed them to custom build proteins and predict how they would bind to the receptor.

The second approach was to design miniproteins from scratch, which allowed for a greater range of possibilities. Using a large library of miniproteins, they identified designs that could potentially bind within a key part of the coronavirus spike called the receptor binding domain (RBD). In total, the team produced more than 100,000 miniproteins.

Next, the researchers tested how well the miniproteins bound to the RBD. The most promising candidates then underwent further testing and tweaking to improve binding.

Using cryo-electron microscopy, the team was able to build detailed pictures of how two of the miniproteins bound to the spike protein. The binding closely matched the predictions of the computational models.

Finally, the researchers tested whether three of the miniproteins could neutralize SARS-CoV-2. All protected lab-grown human cells from infection. Candidates LCB1 and LCB3 showed potent neutralizing ability. These were among the designs created from the miniprotein library. Tests suggested that these miniproteins may be more potent than the most effective antibody treatments reported to date.

“Although extensive clinical testing is still needed, we believe the best of these computer-generated antivirals are quite promising,” says Dr. Longxing Cao, the study’s first author. “They appear to block SARS-CoV-2 infection at least as well as monoclonal antibodies but are much easier to produce and far more stable, potentially eliminating the need for refrigeration.”

Notably, this study demonstrates the potential of computational models to quickly respond to future viral threats. With further development, researchers may be able to generate neutralizing designs within weeks of obtaining the genome of a new virus.

—by Erin Bryant

Related Links

- Immune Cells for Common Cold May Recognize SARS-CoV-2

- Potent Neutralizing Antibodies Target New Regions of Coronavirus Spike

- Experimental Coronavirus Vaccine is Safe and Produces Immune Response

- Potent Antibodies Found in People Recovered from COVID-19

- Unique Genomic Features of Fatal Coronaviruses

- Cancer Drug May Reduce Symptoms of Severe COVID-19

- Early Results Show Benefit of Remdesivir for COVID-19

- Llama Antibody Engineered to Block Coronavirus

- Microneedle Coronavirus Vaccine Triggers Immune Response in Mice

- Study Suggests New Coronavirus May Remain on Surfaces for Days

- Novel Coronavirus Structure Reveals Targets for Vaccines and Treatments

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Coronavirus Prevention Network

- Coronavirus (COVID-19) (CDC)